Patek Philippe has a long history of generously catering to women with exquisite watches, brimming with technological mastery, their appeal often much enhanced by decorations such as enamel work, precious gemstones and engravings. Looking back at nearly two centuries of watchmaking for women reveals some very refined horological treasures along with some interesting stories.

The first watches registered in Patek, Czapek & Cie's sales archives were sold to a certain Madame Goscinska, reminding us that, from the very start, women were attracted to this Genevan house's creations. In those days, the likes of Madame Goscinska would be wearing pendant watches, hanging from a brooch, a chain or an ornate chatelaine, alongside gold trinkets and charms pinned to their dress. These highly visible and very decorative elements of a wealthy woman's attire were as much jewels as they were timekeepers. An early example of this is Patek Philippe's 1840 timepiece, featuring an exquisite miniature enamel painting of the Madonna of the Sedia, surrounded by diamonds. You can imagine the owner treasuring it for both the beauty of the watch and its religious significance.

In those days, few people owned watches, which were a mark of wealth and rank, and even fewer women owned such a piece of advanced technology. So it is no surprise that Patek Philippe's customers included royalty, who usually had their own personal watchmaker to advise them on the purchase of timekeepers, as well as to take care of the clocks and watches in their possession.

Queen Victoria was attracted to Patek Philippe's watches with a keyless winding system and, at the Great Exhibition in London in 1851, chose a powder blue pocket watch decorated with diamonds, set into a pretty and very feminine floral motif. Queens were also known to buy watches as gifts for their husbands. Louise, the Queen of Denmark, commissioned Patek Philippe to create a very personalised pocket watch for her husband, King Christian IX, to mark their 25th wedding anniversary. The double case allowed for a formal enamel decoration of their initials, picked out in diamonds against a dark-blue enamel background. Under this cover, and only visible to the king, was a miniature enamel painting of the queen.

The inaugural wristwatches by Patek Philippe appeared in the 1870s. Unlike earlier adaptations of pendant watches attached to a bracelet, these new timepieces were created specifically to be worn on the wrist. The first of these was sold to the forward thinking and stylish Comtesse Koscowicz of Hungary.

British women were among the first to adopt the idea of a wrist-worn watch as they were practical when hunting on horseback. These models were presented on simple leather straps and, later, gold bracelets appeared at more formal occasions. Despite this new trend, pendant watches were still in demand and reflected the jewellery styles of the era. An example of this is the 'butterfly woman' brooch and pendant watch, in an unmistakable Art Nouveau style, featuring vividly coloured, enamelled wings and sensual, organic shapes.

Men began wearing more practical wristwatches during the Boer and First World Wars, powered by movements originally designed for women's wrists. As the mechanics of smaller movements improved, both men and women began to wear wristwatches. Soon, the ingenuity of Patek Philippe's watchmakers meant that movements were small enough to fit into rings. Creativity flourished around these miniature calibres, which were tucked into many different kinds of jewels, often concealed and elaborately gem-set.

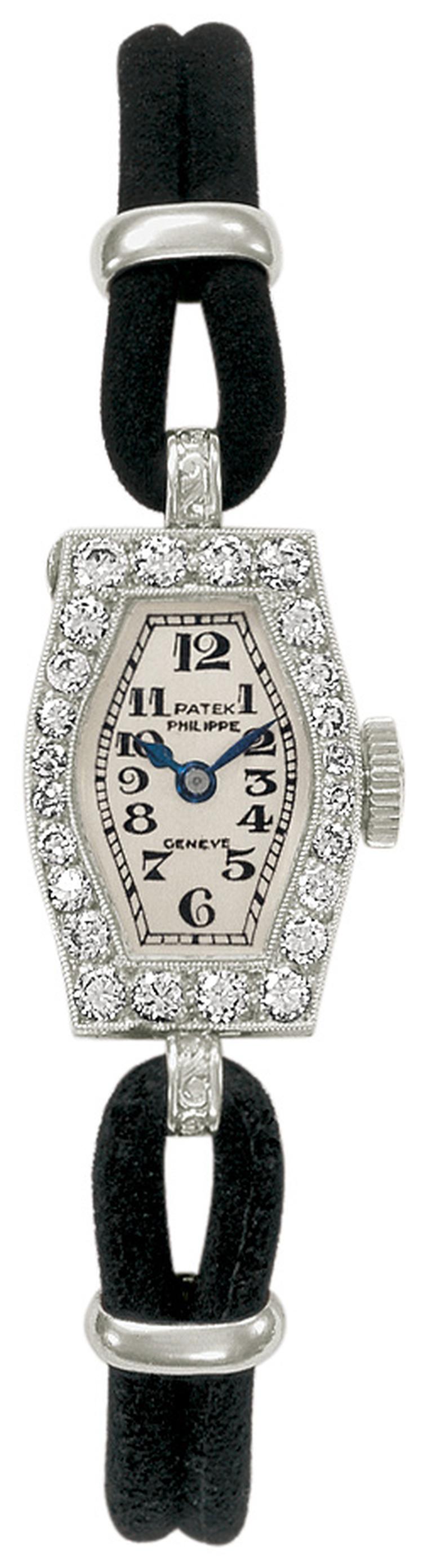

In contrast to the highly decorated and delicate watches of the 19th century, the first decades of the 20th century saw more practical watches for women on robust leather straps. But smaller movements were no less sophisticated than the larger pocket watch versions and, in 1916, Patek Philippe produced a five-minute repeater watch that was sold to a lady in New York.

By the 1930s, the improved precision of scaled-down movements meant the end of the pocket watch, and a wide range of styles were produced by Patek Philippe. It was the Second World War that really convinced women to wear wristwatches, however, as they took over the jobs and roles of men who were away at war.

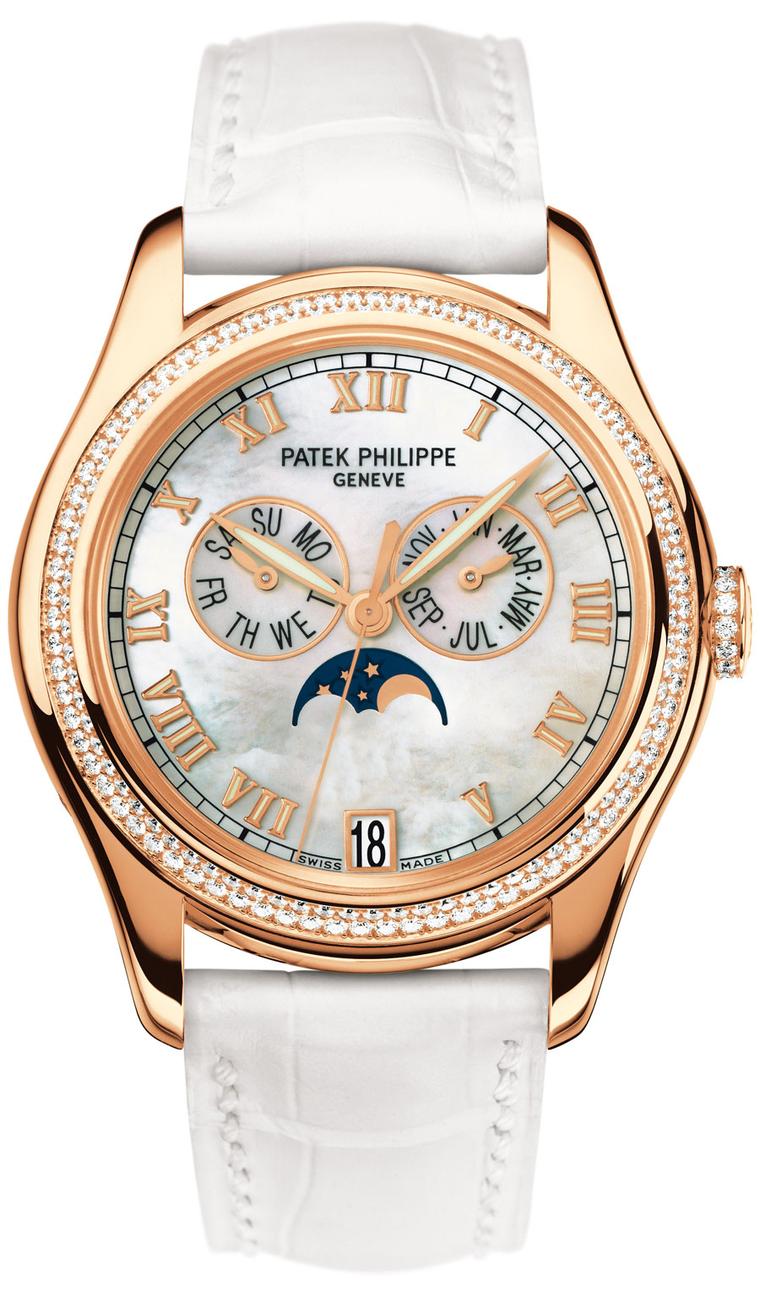

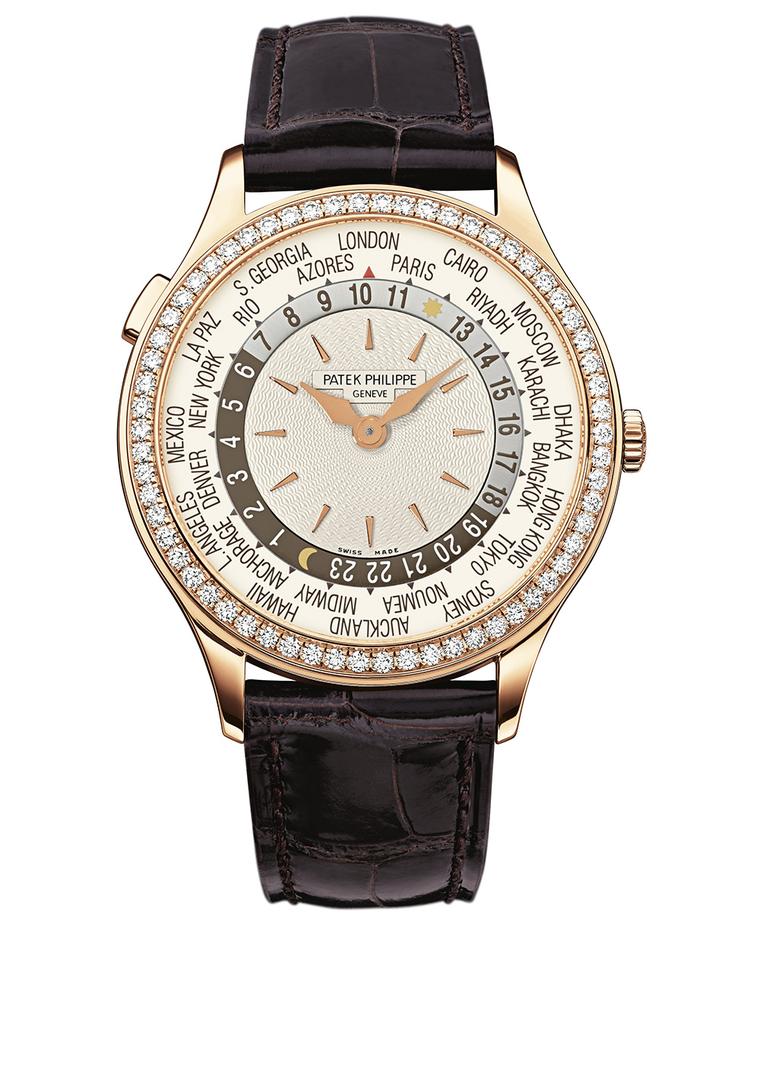

Since then, the wristwatch has been a canvas for creativity and a reflection of changing tastes and styles. Patek Philippe's 1997 Calatrava Travel Time Ref. 4864 was the start of a new era of complex, contemporary mechanical watches for women who can also choose from a range of complicated mechanical watches, including a world time, a travel time, chronographs, a skeletonised movement and an annual calendar. And, of course, the perennially popular Twenty-4 is available in many versions, both mechanical and quartz, with or without diamonds, as are the sporty Aquanaut and Nautilus Lucea.

Perhaps most significantly, Patek Philippe has made an important contribution to the ongoing history of women's watches as, unlike any other watch house, today offers three 'grand complications' in the Ladies First range: a minute repeater, an ultra-thin split seconds single-pusher chronograph and a perpetual calendar. A milestone in the history of women's watches that confirms Patek Philippe's commitment to providing women with the very best.

Read our definitive guide to Patek Philippe women's watches