By Andrew Hildreth

When Thomas Perkins, winner of the 2006 Richard Mille-sponsored Perini Navi Cup and previous owner of the Perini Navi yacht, the Maltese Falcon, announced on US television that he could have bought a tray of Rolex watches for the same price as a Richard Mille watch, it begged the question: why are Richard Mille watches so expensive?

Not long after, Richard Mille himself gave an interview on CNBC in America in which he was asked if he had sold all of the $2 million dollar sapphire crystal watches. “Yes!” he replied. “You have to understand these are very technical watches.” The reporter, bemused that any watch could justify a price tag that high, remained silent. But what did Mille mean by “very technical”? The answer, of course, is complex, and explains why people are willing to part with millions of dollars for a Richard Mille watch.

Read more about other expensive watches here.

Making a case for the case of Richard Mille watches

The first element to consider is the case, and here I am talking specifically about the tonneau-shaped (barrel) case with which Richard Mille established himself. From the outset, when there were only three metals used in case manufacture - white gold, red gold and titanium - there was almost no difference in the price between the same watch in each of the metals.

The sandwich-style Richard Mille watch case is one of the most expensive and difficult to manufacture. Comprised of three decks - front and back bezels, as well as the middle section - each component is curved. There are no flat surfaces to make machining easier and, what’s more, the three curved surfaces have to fit together to within 100th of a millimetre to stop moisture or dust entering.

The use of avant-garde, high-tech materials

The second element is that Mille has started to use case and baseplate materials that are normally used in such realms as Formula 1 cars, aerospace and racing yachts. The materials used are leading-edge technology, even in the industries outside of watchmaking. Not only is the metal or material new in terms of composition, the ability to use them in watchmaking is unknown. Mille dedicates years - and invests millions of Swiss francs - to understanding the material and how to incorporate it in his watches.

Carbon nanotubes, toughened ceramic, NTPT® carbon (originally developed for the sails of racing yachts), silicon nitride, gold fused with carbon and quartz, perfluoroelastomer and all sorts of other alchemist fantasies are concocted to give the watches a unique patina and impressive resilience.

Add to this the real-life crash tests executed by the brand’s stable of athletes including Bubba Watson and more recently the Spanish heptathlete Maria Vicente and you begin to understand at least some of the zeros in the price tag. The new Carbon TPT® strap (above) is the latest addition to the women's RM 07-01 that has 200 components in the strap alone and weighs a mere 29 grams.

For the RM056 series and the RM 07-02 Gemset Sapphire models, where the case is manufactured from sapphire crystal, Mille had to find new ways to polish crystal to the required dimensions of the tonneau case. Polishing flat surfaces is easy, but polishing complex curved surfaces presents a whole new set of problems. The method requires that the surfaces be polished using ultrasound in a pot of viscous diamond-particle filled mud, where the effects of polishing cannot be measured. The failure rate for such a process is high when the three parts of the case have to fit to within the same 100th of a millimetre tolerance. The range of Gemset Sapphire watches now includes blue, green and pink sapphire crystal, this year with an extra dose of diamonds. The sapphire crystal requires 40 days of finishing and twice the time to set the gemstones compared to ceramics or Carbon TPT.

21st-century movements

Apart from the cases, the movements inside are not standard, have usually required a comprehensive redesign and are coated in materials new to high-end watchmaking. Mille never did enter the classical world of Geneva stripes and perlage decorations - his watch movements are coated in PVD (Physical Vapor Deposition) or Titalyt. The movement parts are usually a hybrid of titanium with other materials that Mille’s dedicated team of watchmakers and micro engineers spend years perfecting.

In one instance, for the RM018 Boucheron, the gear train was comprised of wheels created from semi-precious stone that had been placed within a heated brass surround before being fixed as the brass cooled. The research required for such innovations takes years, with dedicated teams of watchmakers and micro engineers.

This may not be the model of the lonely Swiss watchmaker, but then Mille never intended for it to be so. Richard Mille watches are more akin to Formula 1 cars with their cutting-edge use of material science, combining hand finishing with exemplary mechanics and, by necessity, a highly limited production.

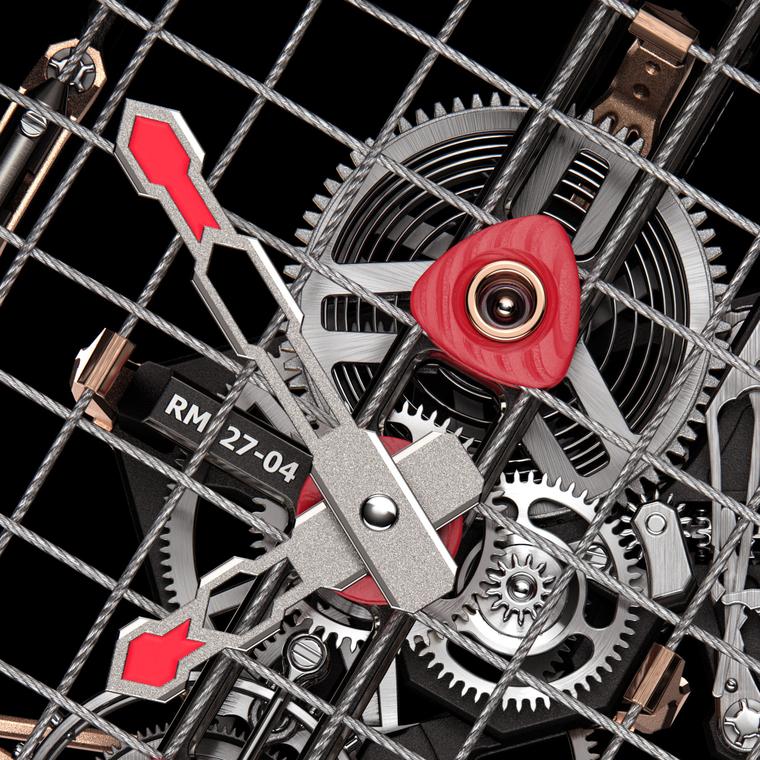

The most recent high profile moment for Richard Mille came on the Philippe-Chatrier Court at the 2020 Roland Garros Tournament. Rafael Nadal took on Novak Djokovic, the no.1 seeded player wearing his new RM 27-04 Tourbillon, a celebration of the 10 years partnership between the player and watchmaker. The case is made of groundbreaking TitaCarb ® which is one of the most resistant polymers on the market with a tensile strength of 3,700kgs per cm2. The 30 gramme watch is capable of withstanding accelerations of over 12,00Gs which was put to the test as Rafael Nadal powered through to win his 13th French Open Victory and 999th career win. Like the strings of a tennis racquet, the tourbillon calibre is suspended suspended in a mesh of 0.27mm braided steel cable. Once again a Richard Mille was on Nadal wrist in another chapter of his relentless rise to the top. The watch has been produced in a limited series of just 50 pieces.

The comparison between a Formula 1 car and a Richard Mille watch is what justifies the price tag. Richard Mille watches are the most expensive racing machines for the wrist. Just like a Formula 1 car, they are far more than the sum of their parts, elevating timekeeping to the highest form of technical art.

Article updated October 2020