The question of provenance is one that looms ever larger in the world of luxury jewellery. No longer is it enough for a jewel to look beautiful; customers also want to know that there are no dirty secrets lurking in its past life, before it is cut, polished and set into a piece of ethical jewellery.

A recent report by Ethical Consumer magazine pinpointed ethical jewellery as a flourishing sector of the rapidly growing consumer market, which is now worth more than £50 billion. Anecdotally, jewellers are also reporting a sharp increase in consumers wanting to know more about the origin of the jewels they are buying.

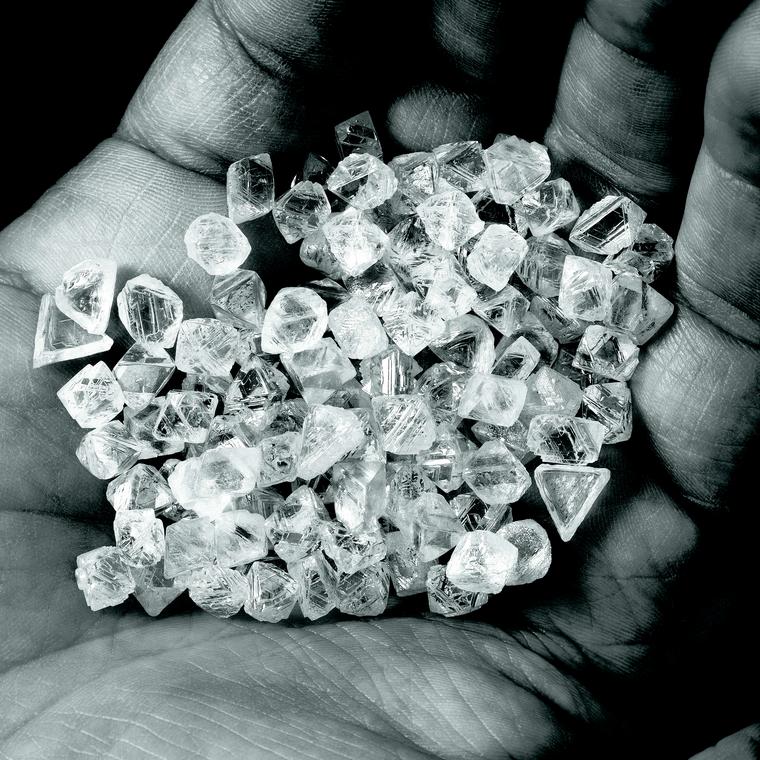

Situated 220km south of the Arctic Circle, in Canada’s remote Northwest Territories, the Diavik Diamond Mine opened in 2003 and now produces around eight million carats of diamonds every year. A joint venture between Rio Tinto, which owns 60% of the mine, and Dominion Diamond Corporation, it is committed to showing the world that diamond mining can be both ethical and transparent.

Diamond-rich areas were not discovered in Canada until the early 1990s, but the country quickly developed a worldwide reputation for its guaranteed ethical and conflict-free stones. All Canadian mines are overseen by the Canada Mining Regulations for the Northwest Territories and each stone is laser inscribed with a unique identification number to give customers peace of mind.

Last December, Rio Tinto hit the headlines when a 187.7ct rough diamond discovered at the Diavik Diamond Mine was unveiled. Named The Diavik Foxfire, it is one of the largest rough diamonds ever discovered in Canada and is likely to yield at least one very large polished stone, destined to be set into a stunning piece of diamond jewellery.

Speaking at an exclusive preview of The Diavik Foxfire, held at Kensington Palace in London, British fashion journalist and ethical consultant Marion Hume recounted her trip to the Canadian mine in March 2015. Referencing the freezing temperatures in Diavik, which can drop as low as minus 45, she described the white diamonds from just beyond the Arctic Circle as “the purest ice from the purest ice”. A long-time champion of ethical fashion, Marion Hume welcomes the wave of demand for sustainability that is currently sweeping across the luxury jewellery industry. She told the audience: “Today, the luxury business is, at last, obsessed with provenance. We want to know where beautiful things come from. We want to know - we should demand to know - that by the time they reach us, they have done no harm.”

Surrounded by lakes, the Diavik mine is only accessible via a 600km-long ice road, which was built by a joint venture of mining companies operating in the area. The winter road is open from February to early April and it has to be reconstructed every year after the ice thaws and with the arrival of warmer weather. While the speed of the trucks travelling to the mines is carefully controlled to protect the ice, the road is very robust and capable of handling heavy loads. Last year alone, Diavik transported 2,757 loads, weighing a total of more than 100,00 tonnes, across the winter road.

In 2012, a $30 million wind farm was constructed at Diavik, with four turbines especially adapted for the cold climate shipped over from Germany. The 100-metre structures were the first wind turbines in Canada’s Northwest Territories and, today, wind energy generates up to 56% of the power needed by the diamond mine, thus reducing its reliance on diesel and limiting the environmental impact of diamond production. Located in one of the most untouched and ecologically sensitive parts of the world, preservation and respect for the environment sit at the very heart of the Diavik Diamond Mine.

An Environmental Agreement drawn up in 2000 between Diavik, the local Aboriginal groups, and federal and territorial governments, sets out the company’s environmental protection commitments. These include working together with Aboriginal elders from the local communities to monitor wildlife, as well as the construction of a water collection system to protect the surrounding lakes, and a coarse rock fill to provide a new fish habitat. In 10 years’ time, when the mine is depleted, the plan is to leave no trace behind of the diamond operation.

It is all a far cry from the old story of diamonds being extracted by rich money-hungry companies at the expense of both the indigenous populations and natural habitats of developing countries. As Marion Hume says, the tide is turning in the global mining industry: “Across the globe now, the diamond business strives to be as transparent as the natural treasures that are its reason for being.”

The long-standing criteria for measuring the quality of a diamond is the 4 Cs - Clarity, Colour, Cut and Carat - with the purest diamonds that money can buy being classed as D Flawless. But given the increased demand for ethical jewellery, maybe it’s time to add a fifth C to those quality standards - Conscience.

With the mine likely to be depleted by 2025, Diavik’s timeline in the history of diamond production may be short but its legacy could live on forever. Hume sums it up: “The best legacy the diamond mine on the frozen edge of the world might aim for is to be DD Flawless: Diavik D Flawless, with all efforts made to be fair.”