By Robin Swithinbank in London

Imagine, if you can, the feeling in your bowels in the final few moments before you start the engine on a car designed to propel you to more than 1,000mph in less than a minute. In 55 seconds, to be precise. There is, let's agree, a good chance of movement.

What you're looking for as your brow moistens and your sinews tighten are assurances that everything's going to be ok. You look to your support team (thumbs up), your own mettle ('I'm the man'), and the equipment all around you (myriad switches, arcane digital displays and a cockpit built to cocoon you from the explosive power of the 130,000bhp generated by the jet and rocket engines behind you) and trust it'll be alright on the night.

And then you see two old-school analogue dials on the dashboard, a speedometer to your left and a chronograph to your right. The sort of thing they had in cars 75 years ago. How do you feel now?

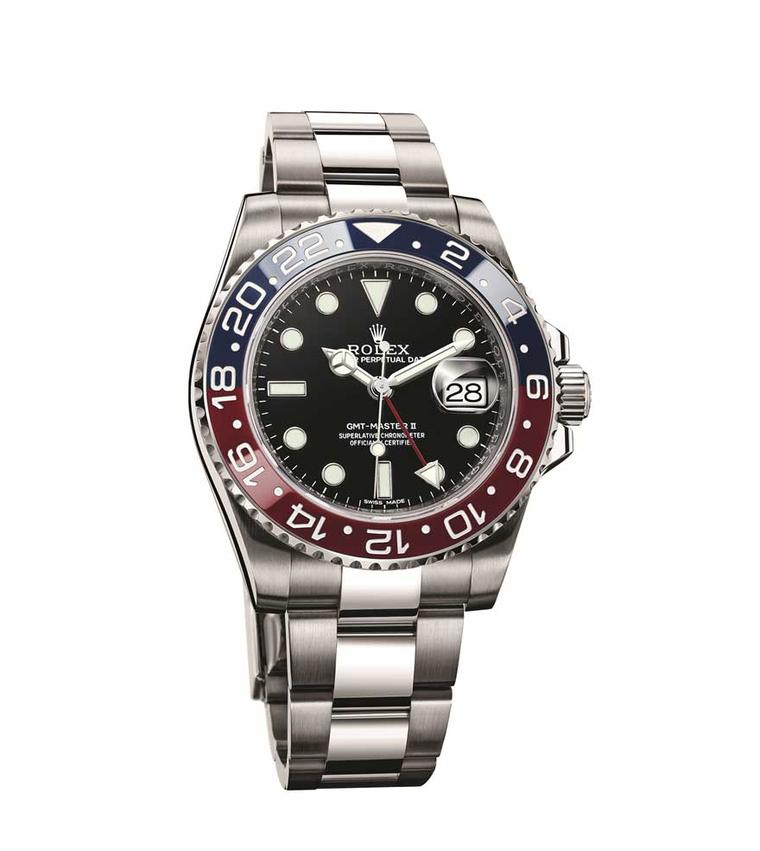

If you're Wing Commander Andy Green OBE and you're at the helm of the Bloodhound SSC supersonic car ahead of a land speed record attempt, and the two bespoke, backlit dials are made by Rolex, the expectation is that you'll feel ok. You asked for them, after all.

Rolex joined the Bloodhound SSC project in 2011 and developed these two instruments for Green, who took Thrust SSC to the current land speed record of 763mph in 1997. The men in white coats have confirmed that analogue dials are easier to read at a glance than their digital equivalents, which is important if you're in a vehicle covering the length of four and half football pitches every second.

Green will use them to time the braking sequences as he hurtles across the Hakskeen Pan desert in the north-west corner of South Africa (planned for 2016), and the critical one-hour turnaround time between the two runs that have to be completed before the record can be made official.

Both instruments have been given a good going over by Rolex to make sure they'll withstand the vibrations during the two runs, and the dramatic changes in temperature deserts are known for. They also have their own power sources so they're good for backup in case onboard computerised systems fail.

Green will be relying on the speedometer to make sure he doesn't overrun the 20km track. At 800mph he can apply the air brake; at 600mph he can deploy the parachutes; and he can only use the friction brake once he's slowed to 200mph. How's that feeling now?