By Ken Kessler in London

Few nations can claim monopolies or near-monopolies on anything. True, certain rare minerals are only available from specific territories, and you can't beat Australia for kangaroos, but the UK is doing its best to ensure that Americans are no longer the fattest people on earth. Italians still rule the world of supercars, but that can be contested by Porsche, Aston-Martin, Bugatti and a few others. French wine no longer reigns supreme. But the watches of Switzerland? The Swiss own the mechanical watch market.

Notice the quick qualifier: mechanical. The Japanese produce so many quartz movements that the sheer numbers manufactured by the likes of Seiko, Citizen and Casio dwarf everyone else's output. But it's not just about numbers. For the past 20-or-so years, the revival in interest in wristwatches, and the concomitant prestige afforded by expensive timepieces produced by Swiss watch brands, have ensured that mechanical watches outshine their electric rivals. Regardless of the gold or the gems that may adorn them, quartz watches depreciate like property in Spain, regardless of who made them.

If a mechanical Swiss movement is both de rigueur for the high-end purchaser and imparts credibility on watches all the way down the price scale to the £110 needed for Swatch's new Sistem51, then the sheer might of Japan (and China) in the electric watch sector has no relevance here. They are to great mechanical Swiss watches what Big Macs are to foie gras. That's not a criticism, merely a statement of their relative status and intent. (If you've ever had a "Mac Attack", then a Big Mac is preferable to foie gras.)

Regardless, the Swiss have performed a miracle by salvaging an entire industry that should have disappeared like the typewriter, analogue TV sets and the VCR due to technological advances. There is no argument that quartz watches tell time with far greater accuracy than mechanical watches, but that misses the point that the Swiss exploited. The best analogy is the continued ascent of the once near-dead vinyl LP in the face of compact discs and other digital music forms: connoisseurs prefer LPs.

So, too, do those who cherish watches favour the mechanical, and almost by default, they buy Swiss watches. When quartz arrived, the Swiss watch industry was decimated. The Japanese mastered low-cost production in the way the Americans destroyed the British watch industry a century earlier, by mastering mass production of affordable mechanical pocket watches.

With the latter situation, the Swiss learned from the Americans. This enabled Switzerland to dominate watch manufacturing for three-quarters of the 20th century when the British and the Americans let their indigenous watch industries die through a mix of malaise, arrogance and idiocy.

By the time quartz arrived, the American watch industry was dead, its greatest names either vanished or - like Hamilton - bought by the Swiss. But quartz caught the Swiss napping, and it would take the sheer genius of the original Swatch to secure a slice of the battery-powered watch market.

There is no reason to think that affordable quartz Swatch alone saved the mechanical watch, as opposed to it saving the entire Swiss watch industry per se. But the funky, plastic Swatch's phenomenal success certainly helped to finance the Swatch Group, which -until recently - provided the vast majority of smaller, independent brands with mechanical movements. The sheer expertise contained within the extended family of the Swatch group, with all of its myriad subdivisions, dwarfs any other country's horological capabilities.

Above all, the Swiss as a nation are clever, hard working, secretive and devious - in a good way. If you look to watchmaking history, you find that the English created most of the important developments that were later co-opted by the Swiss, like the lever escapement and the chronometer and a few other watch essentials. The French drove out the Huguenots, among them the family who settled in Switzerland and would sire the greatest watchmaker of all time: Abraham-Louis Breguet. The same goes for the LeCoultre family. The French, then, sowed the seeds of Swiss watchmaking supremacy.

Having recovered mightily and majestically from the aftermath of quartz, the Swiss regrouped. They salvaged extant brands and revived others. They encouraged the young to enter watchmaking and enabled those watchmakers who still loved mechanical movements in the "lost" years. They're now the 50- and 60-somethings with eponymous brands like F.P. Journe (another ex-pat Frenchman) and Franck Muller.

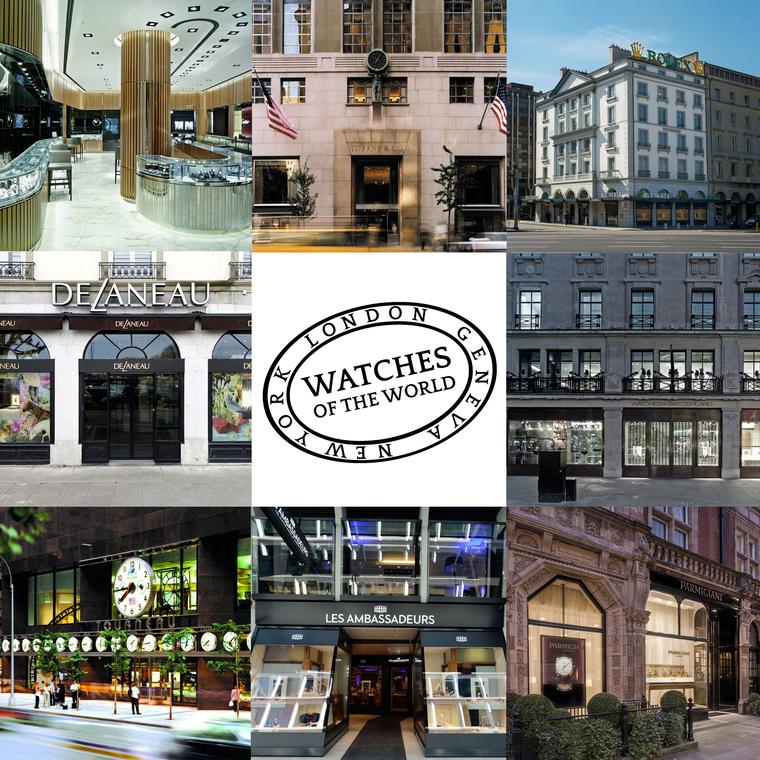

To elevate the prestige of watches, the Swiss educated watch buyers about the challenges of making chronometers and complications. They added style and mystique. Above all, they could exploit genuine history, longevity and experience. The greatest Swiss watch brands Rolex, Patek Philippe, Vacheron Constantin, Omega, Audemars Piguet, Girard-Perregaux, Jaeger-LeCoultre and many others - never abandoned mechanical watches, even during the bleak 1970s and 1980s. They have, rightly, inherited a global market worth many billions.

Challengers? On a tiny scale, there are fine mechanical watches being produced in the USA, Denmark, Finland, the Isle of Man, Ireland and Russia. Grand Seikos, the company's prestige models, are fabulous timepieces. Of late, German independents have been making mechanical watches at both truly affordable and scarily elevated price points. There isn't a watch aficionado alive who would contest the belief that Germany's A. Lange & Söhne and Glashütte Original as categorically two of the finest watch brands on the planet.

Then again, both A. Lange & Söhne and Glashütte Original were revived by the Swiss. And they're Swiss-owned. Case closed.