On 19th June 2019, Christie’s, New York, held an auction of the world’s most magnificent jewels from India. The marathon 24-hour auction included 400 lots from the Al Thani Collection. Led by five different auctioneers, the sale achieved a record-breaking total of $109.3 million. The current expectation is that many of the pieces will appear in museums around the world, giving the public another chance to glimpse the vibrant colours and monumental scale of these jewels.

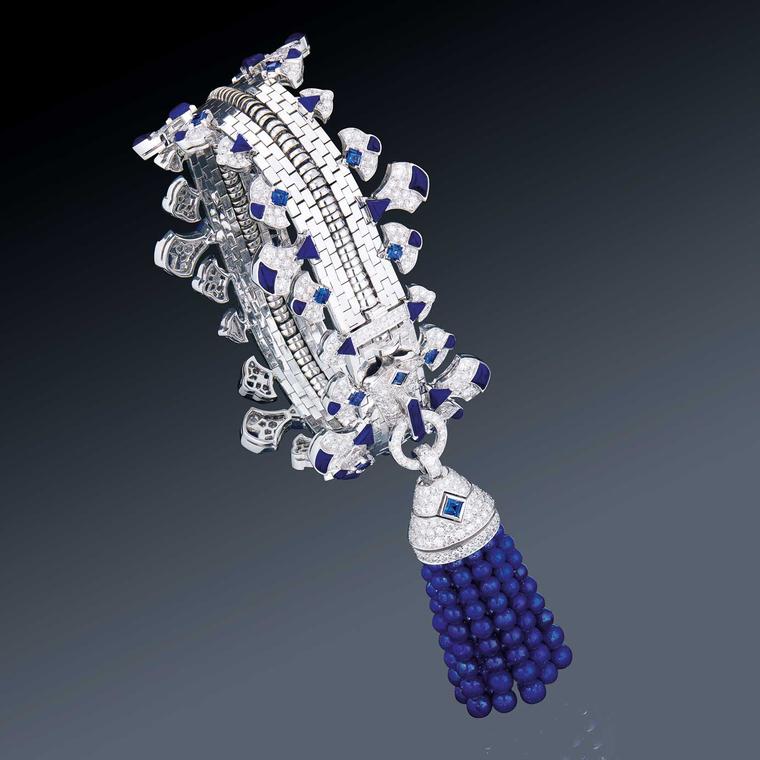

The Al Thani Collection, established by His Highness Sheikh Hamad Bin Abdullah Al-Thani, includes over 6,000 objects of Asian art and artefacts from the ancient world to the present day. Reflecting the encyclopaedic nature of the Al Thani Collection, Christie’s sale included opulent objects from the Mughal court such as a jewelled pen and ink case, rose water sprinklers, and several hookah mouth pieces; but the collection ranged from ceremonial daggers and imperial aigrettes, to Art Deco remodelling of dynastic Indian gems by Cartier and turban ornaments (above). The lots represent less than 10% of the entire collection set to be housed in a museum at the Hôtel de la Marine in Paris in 2020.

Christie’s International Head of Jewellery, Rahul Kadakia, reflected on the auction saying: “Momentum has been building from the international tour to the New York exhibition, culminating with the excitement witnessed in the sale-room.” Sale highlights toured Christie’s London, Shanghai, Geneva and Hong Kong, and attracted international interest with bidders registered from 45 countries on 5 continents. ‘Maharajas and Mughal Magnificence’ tells the love story between India and jewels, from the splendours of the 17th century Mughal court to the present day.”

The sale’s top lot, a Belle Époque devant-de-corsage brooch (top) designed in 1912 by Cartier, Paris, combines rare world-class diamonds and delicate design and achieved a hammer price of $10,603,500. It was made-to-order in 1912 for Solomon Barnato Joel, the director of Barnato Brothers and De Beers Consolidated Diamond Mines. For Joel, diamonds were not only his business, but also his passion. He brought the four brilliant-cut diamonds to Cartier who arranged them in their ‘lily of the valley’ setting. The result was a masterpiece of intricate Belle Epoque style. In the centre of a horseshoe of old-cut diamonds sits a brilliant-cut pear-shaped D-colour diamond of 34.08 carats surrounded by a halo of ‘lily of the valley’ diamond links. Below this central diamond hangs a 23.55-carat oval brilliant-cut diamond on a horizontal axis. The brooch tapers to a modified marquise brilliant-cut diamond framed by identical pairs of smaller round-cut diamonds. The brooch’s floral composition has a delicate elegance that seems to defy gravity.

Diamonds featured heavily in the sale, showing both Indian pride in the glittering produce of their native Golconda mines, and lavish tastes from the Mughals to the Raj. The Mirror of Paradise diamond (above) is a prime example, selling for $5,517,500. This unset D-colour diamond weighs 52.58 carats. Another example of India’s prolific Golconda diamond mines is the Nizam of Hyderabad rivière necklace (c.1890). The graduated rivière necklace (below) is of over 200 carats, with a subtle graduation of rose-cut diamonds sold for $2,415,000.

The encyclopaedic assortment of jewelled objects tells the story of the region’s jewellery tradition. For example, the ancient Indian Kundan technique for setting stones in gold is visible in an enamelled parrot (c.1775-1825), which sold for $1,035,000. The parrot is covered with polished slices of diamonds and rubies to emulate a parrot’s jewel-bright feathers. Kundan jewellery has a unique and distinctive appearance that has become characteristic of Indian goldwork. The jewelled bird, with a large pear-shaped emerald hanging from its beak, is an example of the Mughal love of nature, bold colour and glittering gemstones.

Among the other key pieces of jewellery that exceeded their estimates is an antique Imperial spinel, pearl and emerald necklace (above), which sold for $3,012,000. Seven tumbled spinel beads alternate between clusters of pearls. Below the largest spinel engraved in fine calligraphy memorialising the Mughal dynasty hangs a small emerald.

Mughal Emperors and Maharajas favoured pearls as evident in the long strings of pearls layered on the chests of men and women alike in 17th century Indian portrait miniatures. The iridescent glow of pearls, brought to India by trade routes from the Persian Gulf, were valued as jewels appropriate for men of high rank. Viren Bhagat’s five-strand necklace sold at Christie’s for $1,695,000 is a modern reworking of an ancient form of adornment for Indian nobility.

The Shah Jahan Dagger (above) , with its exquisitely carved jade handle, is a testament to the skilled craftsmanship and multicultural nature of artefacts from the Mughal Golden Age, and is of the same ilk as the Taj Mahal and the legendary Peacock Throne built under Shah Jahan’s patronage. The dagger reveals the fusion of European art in the naturalistic carving of the human head and Persian culture in the inscriptions. The presence of Islam in India can be detected in the scrolling designs inlaid with gold across the top of the blade. The trade routes with China supplied the jade for the dagger. The dagger’s delicate shaft speaks of the luxury of Shah Jahan’s court and the intricate attention to detail lavished on royal objects. The dagger now holds the world’s highest auction price for an object once owned by Shah Jahan, reaching $3,375,000.

The broad cross section of jewelled objects from the Subcontinent auctioned at Christie’s illustrates the magnificence of the 17th century Mughal court while contemporary designers such as JAR (above) and Viren Bhagat reveal the enduring role of Indian decorative culture on jewellery.

By Ottilie Kemp